La distinction entre le naturel et l’artificiel semble s’estomper progressivement, brouillant ces catégories qui structuraient notre rapport au monde. Cette confusion redéfinit nos interactions avec notre environnement, et façonne de nouvelles constructions conceptuelles. Notre langage et nos comportements s’adaptent subrepticement à ces nouvelles logiques, jusqu’à transformer notre expérience du monde. Ainsi, nous disons sans hésiter « mon téléphone est mort », comme si l’usure d’un objet technique relevait du même ordre que la fin d’un organisme vivant. Ce glissement n’est pas une simple figure de style : il témoigne d’un rapport aux artefacts où la frontière entre l’animé et l’inanimé, entre le vivant et le non-vivant, devient poreuse.

Dès lors, la question de savoir si un agent, par essence, appartient au registre du naturel ou de l’artificiel semble perdre de sa pertinence. Ces catégories se dissolvent dans un enchevêtrement toujours plus complexe, où le biologique et l’électronique, le vivant et le synthétique, se confondent et s’hybrident. Ce n’est donc plus tant l’essence d’un objet qui importe, mais le type de relation que nous entretenons avec lui.

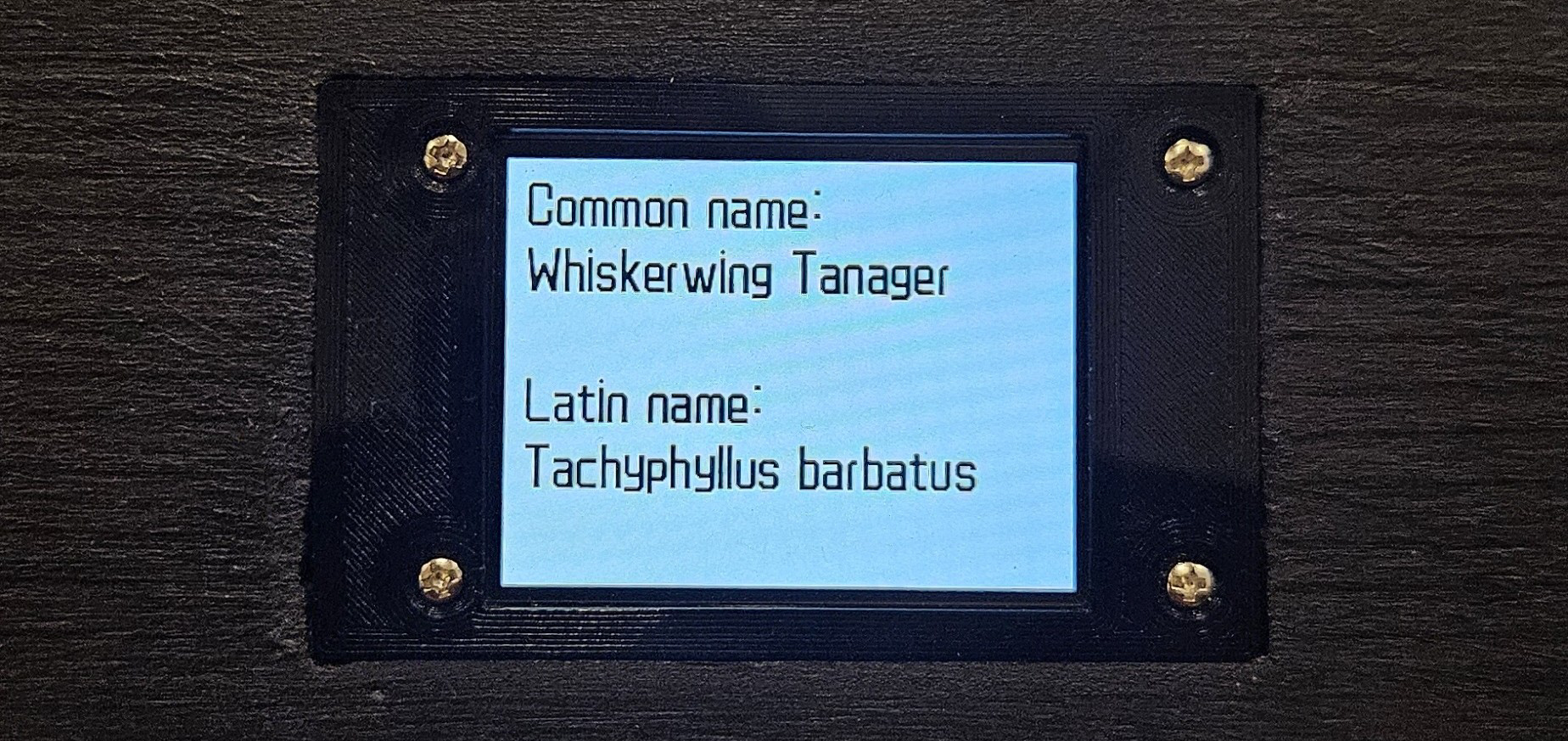

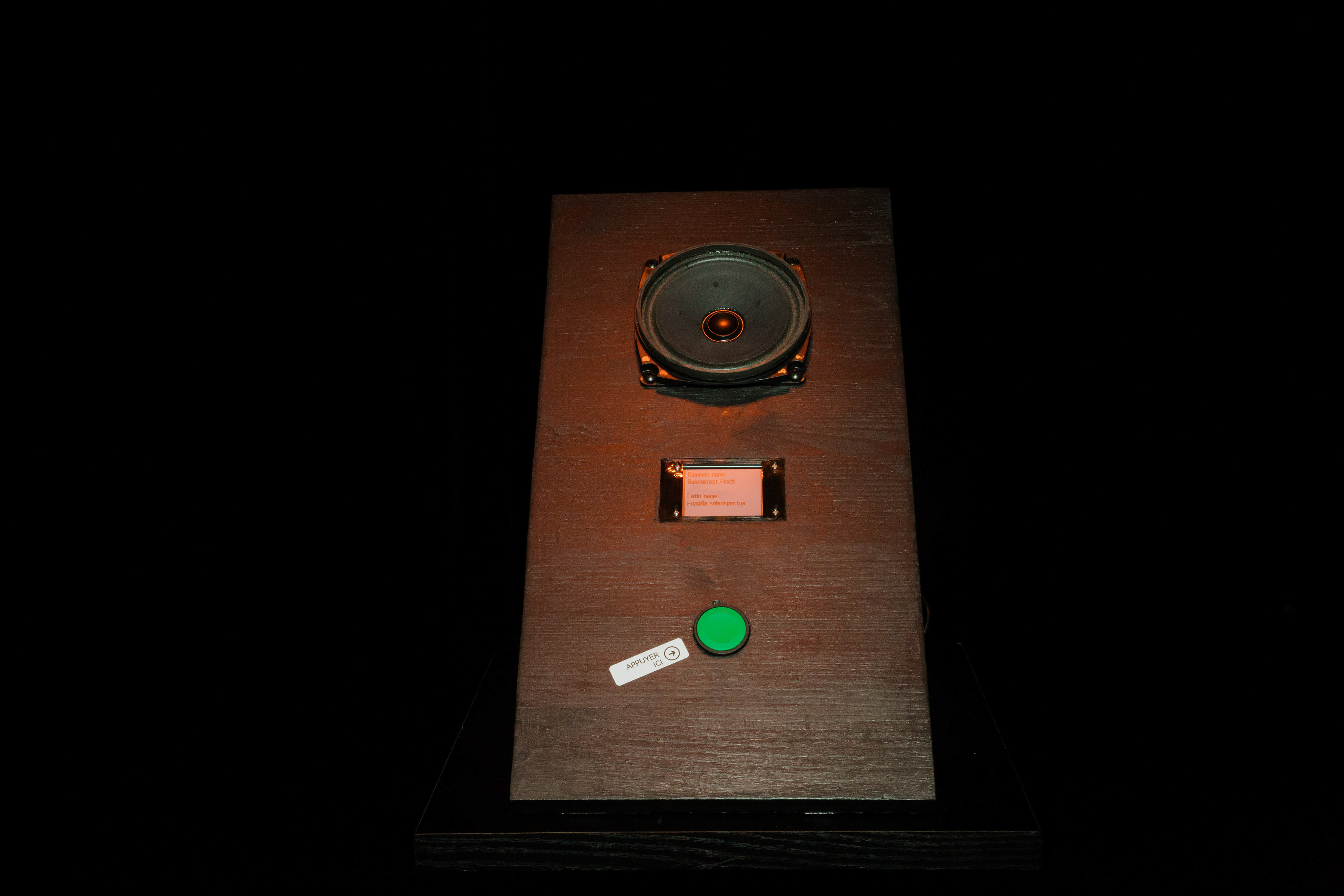

L’œuvre « Un oiseau ? » met en scène cette ambiguïté. Lorsqu’on appuie sur un bouton, un haut-parleur émet le chant d’un oiseau qui n’existe pas, généré artificiellement par un processus algorithmique. Sur l’écran s’affichent un nom commun et un nom scientifique, tous deux inventés. Ces sons et ces noms, bien que dénués de référents dans la nature, existent néanmoins : ils prennent forme dès l’instant où ils sont perçus. Et parce qu’ils sont crédibles, ils peuvent même engager la même expérience sensorielle qu’un véritable chant d’oiseau. L’illusion opère non pas en dépit de leur artificialité, mais précisément grâce à elle.

Ainsi, « Un oiseau ? » ne se contente pas d’imiter le vivant : il en révèle les mécanismes perceptifs, explorant la manière dont notre esprit reconnaît, interprète et investit de sens ce qui lui est donné à entendre. Il questionne ce qui fait qu’un être, ou un son, peut être reconnu comme vivant.

The distinction between the natural and the artificial seems to be gradually blurring, blurring the categories that used to structure our relationship with the world. This confusion is redefining our interactions with our environment, and shaping new conceptual constructs. Our language and behaviors adapt surreptitiously to these new logics, to the point of transforming our experience of the world. For example, we say without hesitation “my phone is dead”, as if the wear and tear of a technical object were of the same order as the end of a living organism. This slippage is no mere figure of speech: it testifies to a relationship with artifacts in which the boundary between the animate and the inanimate, between the living and the non-living, becomes porous.

From then on, the question of whether an agent, in essence, belongs to the register of the natural or the artificial seems to lose its relevance. These categories dissolve into an ever more complex tangle, where the biological and the electronic, the living and the synthetic, merge and hybridize. It is no longer the essence of an object that matters, but the type of relationship we have with it.

"Un oiseau?" brings this ambiguity to life. When a button is pressed, a loudspeaker emits the song of a non-existent bird, artificially generated by an algorithmic process. The screen displays a common name and a scientific name, both invented. These sounds and names, though devoid of referents in nature, nevertheless exist: they take shape from the moment they are perceived. And because they are credible, they can even engage the same sensory experience as a real bird song. The illusion operates not in spite of their artificiality, but precisely because of it.

In this way, “Un oiseau?” not only imitates the living, but also reveals its perceptive mechanisms, exploring how our minds recognize, interpret and invest with meaning what is given to us to hear. It questions what makes a being, or a sound, recognizable as alive.